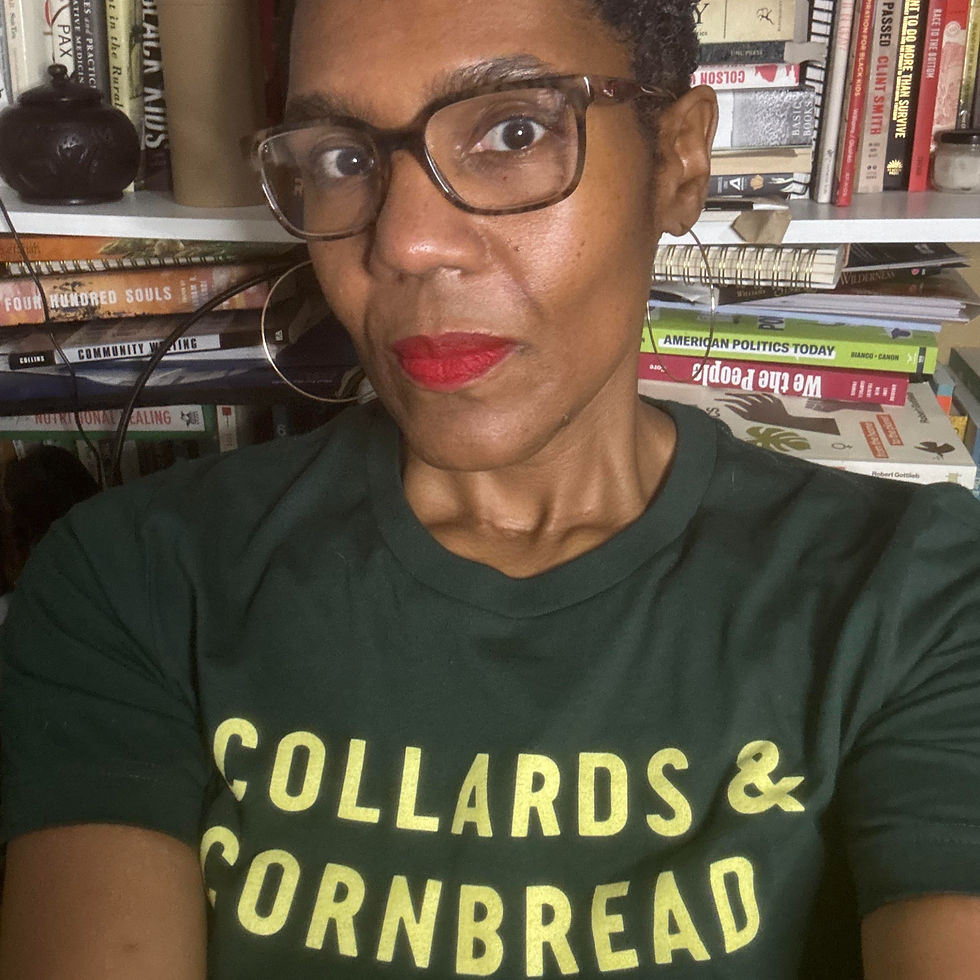

Friday Feature: Leslie T. Grover

- Nov 21, 2025

- 11 min read

Leslie T. Grover is an award-winning writer, scholar, and activist. Her novella, The Benefits of Eating White Folks, marked her entrance into historical fiction, following her work in academic and nonfiction writing. A southern Black writer, her short stories have appeared in Waxing and Waning Literary Journal, Testimony, and as the winning entry in Owl Hollow Press’ The Takeback Anthology. In 2024, she won Amazon Kindle Vella’s Grand Prize for her short story, “Little Girl.” She is managing editor for PushBlack, a media organization dedicated to uplifting Black history through storytelling. Leslie currently lives in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Pennies

June 10, 1966

Dearest Deborah,

Mama mad she had to bring me all the way home and wait for me to change my clothes. Daddy say she may as well go on and take me back now since it’s gone take a while for the men to get the bags ready. Then by the time we get back, we can do what we came to do and all go home.

Miss Melba say Mama never should of trusted me to get dressed by myself anyway and out of all days, why she choose this one to let me run wild and almost mess things up for everybody?

“I’m yo best friend,” she say to Mama right in front of me like I wadn’t even there, “and I’m gone always tell you the truth even when you don’t want to hear it. Truth is that girl ain’t right and you know she ain’t right. You got to watch her close.” She cut her eyes at me like I didn’t understand what she was saying.

But I did understand, and I didn’t need no watching. When they said we was doing important business, I put on my going-to-town clothes, same as Mama and Daddy do when they go to the bank to handle important business.

I was glad when Mama, Daddy, and Miss Melba went on ahead of me. And sister, I did my best to do right. I did just like they do, everything I know to do. I did just like I do when Mama standing right there in case I forget.

I even did like she say and put on my good draws. You how she always say, “Wear your good draws when you go out so in case something bad happen, the folks won’t be scared to touch you.”

Important business means we dress up. But when I got there they was wearing work clothes. Maybe they the ones ain’t right because they can’t make up they minds. Seems to me they should be mad at they own selves, saying business but look like work.

When Mama get mad, she press her lips together, close her eyes, and breathe in. “Lord have mercy on yo child,” she say, clasping in her hands like she finna pray. Then come the tears, but she don’t let them stream down her face like she do when she catch the Holy Ghost. She wipe ‘em fast and stay quiet a long time.

You know how she do.

It’s already enough crying round here, anyway, especially at church. All the women been wailing and fanning since the New Year and saying Lord Hammercy and don’t none of them have the Holy Ghost. It’s because seem like every month the white folks go crazy. They done hung somebody from a tree on the court square. Beat somebody in a ditch off the main road. Shot somebody over by the county park. Anything to try to scare us. It’s already five dead since January.

It’s the summer now, and Uncle Asa make number six.

Mama been quiet, all full up with tears that don’t fall, ever since they found Uncle Asa all beat up and laid out in the ditch beside the big Welcome to Our Friendly Town sign.

That was two weeks ago.

“It’s too much,” she say to Miss Melba. “They didn’t have to do him like that. He ain’t do nothing but try to vote and we all got the right to do that. It’s the law. And we citizens. Even President LBJ hisself signed the law that say they can’t do nothing to keep us from voting.”

She press her lips together again.

Now our whole family got to scrape together enough money to get the body from the county and get Uncle Asa buried. And I know Mama ain’t said nothing, but we got to pay an extra fee. The sheriff say Uncle Asa officially died on public property. He say it take public taxes to clean up the mess.

“Y’all Nigras don’t want to work for free,” he say, looking like he bout to bust out laughing, “So why should my deputies and the county workers?”

The longer we take to pay, the more we owe.

Daddy say it just ain’t right to kill a man for exercising his rights. Say if Uncle Asa fought in the war against the Nazis, and it was just fine for him to get his knee blowed out, then why he can’t limp on that same knee to get his self to the voting booth?” Daddy balled up his fist and banged it on the dinner table. “The devil is a lie and that sheriff giving him work if he think we gone sit around, watch white folks hang us, chop us up, and then pay for them to clean up they mess,” he say. “My brother always stood for what was right. He never woulda stood for this monkeyshine.”

But Daddy don’t press his lips and get quiet like Mama do when he mad.

His face turn red, and the veins in his neck poke out like the fat brown worms we catch catfish with. And he keep saying it everywhere he go, too, not just at dinner. At his lodge meeting. Up town at the Big Store. Downtown at the feed store. When he and Mama play spades with Miss Melba and her male friend from over in Mound Bayou.

“We paid those poll taxes together. We learned those law questions for the test together,” He say at the church meeting last week. “These white folks around here eating us alive and either we gone stand up or get rolled over. How many more bodies we got to see before we make a move against this foolishness?” Folks clapped and said amen.

Daddy, Mama, and all who got a dead family member got together and decided to stand up. That’s why we was all down at the county courthouse in the early morning hours before they open, waiting on the sheriff’s office to let us in.

“We gone show them we mean business,” Mama say.

We all know the sheriff and those men in the long white masks are the ones killing any Negro who try to vote. The white folks say it’s wrong for us to vote, regardless of the law. Say that federal law don’t apply if local law don’t agree. And anyway, the sheriff say when he come up to the church a few days after LBJ sign the law, ain’t nobody gone enforce it, so we may as well work together. Can’t we find a way for everybody to get along? Nobody clap or say amen. The whole church just look at the sheriff until he clear his throat. He finally leave, slinking like an old chicken snake to the back door.

“I know y’all don’t want to hear it,” he put on his hat. “But I’m just trying to see that the right thing is done. And we right about this, hard as it is for Nigras here to face. Don’t y’all want to do right by God?”

But if the white folks so right about everything, then why they cover their faces when they out tryna scare us? The sheriff ‘nem act like they shame or something. If it wadn’t right why they kill us about it? Ain’t that wrong? Why not try us in court and drag us through the law process? Or why not leave it to God if he on they side? Why come none of the white folks can tell us where in the Bible it say Negro folks can’t vote?

I may not know school books, but I know the Bible do talk about love, justice, and treating thy neighbor as thyself. It say thou shalt not kill, too.

Mama say a lie don’t care who tell it, and that all them folks is lying about God. But I think the truth don’t care who tell it either. Truth is Uncle Asa body still there on the cooling slab at the county in the back of the jail, and the sheriff and the other men under those masks put him there.

If we want to get Uncle Asa from up at the county, we got to pay $10, plus the cost of digging a grave in the church graveyard, plus that clean up fee. That’s close to $25 if we pay on time. If we don’t, we gone end up owing even more. When Daddy ask why more, the sheriff say the family owe an inconvenience fee. But the county ain’t the ones being inconvenienced.

We is.

Every time somebody get killed by the sheriff and his men, the church pay half and the family pay half. But with so many dead now, the church had to collect at least $250 to bury all them dead Negro bodies properly.

It take almost a year to earn an extra $25, especially when the prices at the feed store keep going up. Miss Melba say eventually all of us working around here will earn that land we farming on.

But I think she wrong. Truth is, every time we pay things off, the prices go up, and we still owe the white folks. Or they say we ain’t picked the right weight of cotton. I ain’t say much to Miss Melba, Mama, or Daddy, but seem to me them farmers tricking us back into working they fields for free, except this time they don’t call us slaves to our face.

Maybe I ain’t right in the head, but I know all about cotton because I used to help Daddy pick it. I can look at a whole field and tell how much every piece gone weigh when it all go to the gin at the end of the day. I ain’t never been wrong. Not once. So when they say we ain’t picked enough to cover costs, I know that ain’t right. I tell Daddy that and he look at me funny. So now I don’t say nothing.

The sheriff say some of us high-falutin' Nigras like Uncle Asa too ornery to see that it’s easier to let things stay the same. We should just keep paying the poll taxes or not vote at all. “That poll tax ain’t but $2.00,” he say to Daddy at the Big Store one day. “Over the last few years, all the Nigras that done got killed in the county come to at least $1500 in total. So if you can’t figure out the difference between $1500 and $2, that just proves you too gullible and misinformed to vote. The white folks here is good God-fearing christians and trying to do right by y’all. Ain’t we done always took care of you? Ask Asa that.”

When Daddy shake his head and walk off, the sheriff holler behind him, “All we gotta do is trust God and things will be all right! When y’all stop we all stop!”

Uncle Asa ain’t never stop, though. So the sheriff ‘nem stopped him themselves. And they still trying to stop us even though Uncle Asa dead. The sheriff say somebody gotta pay what’s owed for them bodies or they gone have to start taking land or cutting down on the food they order for us to eat during the cold months when farming don’t pay. But them farmers don’t even pay for it since the government gives them surplus food direct. They supposed to give us that as part of our payment for working the land. And last year they ain’t gave us none of what we earned. But white folks can do mess that.

We can’t.

The Greens and the Johnsons took they people’s bodies and left. They put them in the ground and headed right up to Chicago. No funeral. Nothing. They say they ain’t paying a thing, no matter what the sheriff say. Say if the county want the extra fees, then let them come to Chicago and take it out they hands directly.

Now it’s Krafts, Grants, Boatwrights, and us left to pay up because we ain’t going nowhere. Daddy say to let them others go up north if they want to, but we ain’t eating cheese and we ain’t running neither.

“All the scared Negroes run north,” he say to Mama.

When I showed up this morning, there was way more people there than just our few families. The congregations of all the Negro Baptist churches from the next county over came to stand with us. All the AMEs came, too. Then came the ones that don’t even go to church. Even the lady who sell Miss Melba her love perfume and burn hair to make folks sick was there. Some brought extra money.

Anyway, the day before Daddy and some of the men went to banks down in Jackson and got all that money turned into pennies. I ain’t never seen that much money in my life, but it was so many pennies, the men had to bring they trucks to help carry it. They stayed up all night putting pennies in cotton sacks.

That’s how we gone pay it all for everybody, $2800 in pennies including them clean up fees.

“Today we gone dump them pennies on the front desk in the sheriff’s office and tell him to count it his self,” Daddy say to the crowd. “That’s what the law say. So since the county all about business, the business of killing us over our rights is gone get harder and harder to carry out. So all who going with us, let’s line up and get ready. Kraft, Grant, and Boatwright families come to the front with us.”

Don’t that sound like business to you? So why they got on working clothes and making me change out my clothes? I was gone ask Mama on the way back home, but Mama don’t listen to nothing I say, especially when Miss Melba get to chirping in her ear.

Mrs. Kraft and Mrs. Boatwright both old church mothers, and they can’t walk, so Daddy send for the young men to bring them in chairs from the lodge. At first he tell Mama just let me stay and wear my good clothes because it don’t matter what I got on long as I can carry pennies. But Mama gave him a look and then he say by the time the young men get back, me and Mama need to be back, too.

Mama say she gone to check Miss Melba’s stove and make sure it’s off and see if the old tom cat got out the house. I better be ready in my right clothes when she get back. Not in my good dress but in the same overalls I chop cotton in. She say I bet not move til she get back, either. Soon as I got in, I changed real quick. I been sitting here for a long time writing to you.

I want to go to Miss Melba’s and catch Mama, but I’m gone wait like she said to. I don’t want no more trouble. She might make me stay back. Them pennies ain’t gone carry they selves to the courthouse. I shole want to help.

Take care and don’t forget about us while you up there at Valley State. I ain’t that smart, but you is, and I am real happy you learning how to be a good teacher. Maybe you can come home and help me get better with school books. And just maybe by the time you come home, them county folks’ll be through counting our pennies.

Love your big sister,

Berenice

###

Torch Literary Arts is a 501(c)3 nonprofit established to publish and promote creative writing by Black women. We publish contemporary writing by experienced and emerging writers alike. Programs include the Wildfire Reading Series, writing workshops, and retreats.